The nature of wind energy is important to take into account when you're planning to capture and utilize it. Too small a unit won't capture enough to do a lot of good, and too large a unit is too expensive to make sense: you would be better off investing the money and paying your electric bill with the interest. :-)

Because wind power is not particularly reliable over the short term, the storage/use of the power has a lot to do with how much good you'll get out of it. Your situation will determine what best to do with your wind power.

First let's see about actually capturing some energy.

The amount of energy in the wind is proportional to the cube of the speed. You can check wind maps for the U.S. or your area of the world to see how much energy you're likely to get out of the wind in your area. Try here, here, and here. High winds are great; low winds mean that you'll need a larger prop, since the larger the prop, the lower the windspeed it will work well with.

The amount of energy your prop gets is proportional to the area which is covers when it rotates. This is proportional to the square of its length.

You may ask why you shouldn't make as large a prop as you possibly could. The limits on the size of the prop are (1) how it is constructed (since larger ones will want to fly apart), (2) how large a generator/alternator you can afford to hang off of it, (3) how you're going to regulate the speed of it in excessive winds, and (4) how high you can mount it. Let's take each point in turn, since you probably want to build as large a unit as you can without running into these limitations.

Smaller to medium sized props can be made with wood if you have the appropriate tools. Larger ones tend to be made of fiberglass, and the largest are carbon composites.

Here's a picture of how I mounted my prop onto a 1" shaft. I welded 1" collars on rectangular plates and put one on each side of the prop and they seem to do a good job.

There are many good pages on the internet discussing how to make blades, so I won't attempt to duplicate all of that information here. Let me just give some useful general figures and facts, and suggest that you visit my calculations page, found at the end of this page, when you're ready.

The faster the prop spins, the more energy it can collect from the wind. As a practical matter, though, you probably want to shoot for a TSR (tip-to-speed ratio) of 5 or 6. This is achieved by the outer half of the prop having about 5 degrees of "attack" from the plane of the prop. This means that the flat side of the prop has this angle; of course this angle becomes greater (usually up to the maximum attainable for your particular thickness of wood) near the hub of the prop, within reason. The hub is greatly stressed and it's preferable to leave a little extra material here than to try to use the little bit of wind that this area of the prop covers.

If you want 5 degrees of angle in your blade then you will have a slope of 1:11. If you merely take a 1"x4" plank of wood and make the flat side of the blade run from one corner to the opposite (diagonal) corner then you'll end up with a 12 degree angle, which is a fairly slow-turning and inefficient prop. In any event, the slope is determined by the tangent of the angle you'd like to achieve. tan(5) = .087, let's say .09, and 11 of those will fit in 1, so this gives a 1:11 ratio. Using our 1"x4" plank example (and the true dimensions of a 1"x4"), .75 / 3.5 = .214, which is about the tangent of 12 degrees.

Here are a few rules of thumb for the shape of the airfoil.

The thickest part of the airfoil should occur 1/4 of the way back from the leading edge of the blade. The thickness of the blade at this point should be 17% of its width at high angles of attack (like near the root) and 12% at low angles of attack (like near the tips). The width (chord) of the blade should taper from the root to about 1/2 that amount at the tips. However, if you are making a prop which really doesn't have enough blades to capture the wind fully (the blades should cover about 10% of the swept area) then I wouldn't give the prop this taper.

The bottom of the airfoil (the side that faces the wind) should be more or less flat, with a twist. At the root the angle should be as great as possible (up to 30 degrees) given the thickness of the blade, with the outer half of the prop generally having an angle of 5 degrees (vary according to position of course). The leading edge should be rounded so that the point farthest forward is 25-35% "high" from the flat bottom of the blade toward the thickest point.

If you have more time than money you can maybe cut your own prop with hand tools. I happen to have a few tools around, some courtesy of my father, and I found it possible to use a table saw to take off most of the material from the blades, then use a planer (power table-type) to do most of the shaping. A hand-held belt sander finished things off and the prop worked pretty well for a first effort. Due to a knothole near the hub, I hung it up on the wall instead of trying to use it for the long term.

Taking one table off of the planer made for fairly easy going, and I was able to do without the table-saw setup, which was a bit difficult to control. I made 2 props, an 8-footer and a 6-footer, each taking about 2 hours. The first step was to taper the chord, and although I used the planer, a saw could have done most of the work. In any event, next came the forward (flat) surfaces, with their associated concave cuts near the hub. Lastly was the rounding off of the "tops" of the blades.

I removed one of the tables from the planer so I could make the concave cuts near the hub of the blade.

This hand-held power planer is great; it leaves wood quite smooth and is easy to use.

In my meager experiences building props, I have found that, in general, my errors have been along the lines of giving the blades too much angle and leaving them too thick. A small 2 foot diameter prop I made for a small permanent magnet motor turned quite pitifully, for example, until I removed most of the thickness I'd left on it, after which it turned about 4 times as quickly. It's certainly tempting to leave lots of angle, to get balky devices turning in low winds, or to leave too much thickness, to achieve strength, but you can see how these defeat the purpose of the prop in the end.

Look at page 7 of this file, or this page, for a nice table giving a guide to alternator size as a function of prop size, at "reasonable" wind speeds. There is another important table, on the same page, which gives the rough angles the blade should have to give an appropriate speed of rotation versus wind speed (called TSR, the tip-to-speed ratio). As a rough guide (tables exist for this, too) a 6-foot prop should turn at about 500 RPM and a 9-foot prop should turn about 300 RPM. This will give you some idea what you're up against when coupling various alternators to your blade.

A common way to slow the blades down that you'll often see mentioned is to load them down with the alternator. If your alternator is too small for your blades, all this will do is burn your alternator out. But with reasonable matching, this can be a good way to prevent overspeeding. Often a simple wind-speed switch of some sort will turn on a relay or the like which will connect a normal electric space heater (or equivalent) to the alternator, which is enough of a load to slow down the average runaway wind turbine.

Changing blade pitch is great if you're working at that scale; many very large wind turbines have adjustable pitches to take the best advantage of varying wind speeds. But most small wind turbine builders will not opt for such a complication in the design, because the payback at small scales is not great enough.

A popular method of speed regulation is to turn the blades out of the wind. This can be done manually, or, preferably, automatically. Manual tasks can occasionally not get done at crucial times, though, so I'd recommend at least some forethought about how to make this automatic. :-)

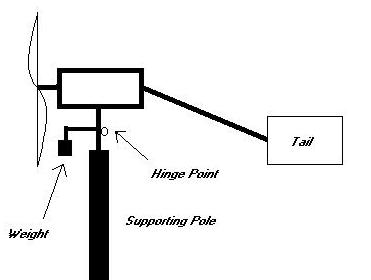

Automatic turning has been done cleverly in several ways. One way which strikes me as being simple is that the entire unit is hinged somewhere and held in place by its own weight or by springs. When the wind presses too much upon the front of the assembly, it "gives" at the hinge point. This might require a bit of experimentation with hinges and springs when you're testing your unit out, but I like this idea and think that it's fairly simple and reliable. It's better to avoid putting the extra power into the whole system to begin with than to accept the power in and try to dissipate it later. The down side of this is that the gyroscopic forces upon the blades and the rest of the unit can be quite significant, since the wind is trying to change the plane of the prop at just the time that the prop is spinning its fastest. Maybe an old car shock absorber would help here?

The "furling tail" arrangement consists of mounting the prop a bit to the side of the vertical axis of the mounting pole, say a few inches. This produces a bit of a turning force on the whole unit, but of course the tail is mounted in the normal manner, aimed just a bit to the other side if necessary, producing the same amount of force the other way.

The key is to make the tail boom "break away" when enough of a turning force is present on the unit because of high winds. The prop then turns to the side of the vertical mounting pole which it pivots on and no longer faces the wind straight on. The tail also turns and the effect is to fold the prop and the tail together.

Some sort of hinge and spring arrangement would probably suffice. You can also mount the hinges at an angle off of vertical, say 30 degrees, so that whenever the tail moves to the side it also moves up at that angle. That makes the weight of the tail itself provide the "springing" action. Of course the angle has to be adjusted depending on the weight of the tail, offset of the prop axis, etc., but this is doable and reliable.

I myself prefer real towers, to allow for plenty of fooling around and regular maintenance. You can put a fairly large wind generator on even the smallest tower. A 60-foot tower is easy enough to put up with a bit of work and a few bags of concrete. Of course, at $100 per 10-foot section, even small towers are expensive when new; I get mine used by asking around and taking them down myself. "Real" towers are safe, useful, and a joy to own. See my towers page for more information on towers.

I installed anchor bolts from the local home supply store into a regular phone pole and plan to put a turbine up there. This one is about 25 feet high. Next to it is the "test stand". I've hung a car alternator off of the 8-foot blade with a 12" pulley I made myself out of a couple of pieces of plywood. The winds are 25mph today and so the unit is really whirring away! However, to tell you the truth, this prop doesn't usually get this alternator turning very well, and should probably have 3 or 4 blades. However, there is the advantage of being made out of single piece of wood (the 2" x 6" plank) and the prop is therefore quite strong. I have let it turn freely in 30-35mph winds and it hasn't come apart yet! Of course, all the energy is dissipated into noise.

I have made a wind turbine out of a ceiling fan and have just made a mounting for it. Hopefully I can see how it works soon. It's the typical ceiling fan motor, which is an inside-out induction motor. As with most induction motors, it should require a larger capacitor than is already present to behave well as a generator. I am hopeful that this approach will work well, since these motors have many poles and usually operate from 500-1000 RPM, and should therefore generate electricity at around these speeds with a prop directly attached.

The results? So far I have never managed to turn the electric meter backwards. Either it's something about being on the "slow" setting or not having a large enough capacitor; I haven't figured that out yet. I'll keep you posted.

From a mechanical standpoint, the type of front wheel spindle which appears to be ended by a flat plate (which is bolted to car suspension parts) is quite convenient. You can bolt the spindle to anything you please, and of course it's going to be solid; it was a critical part of a car! Moreover, this sort of spindle will take end loads (because of the tapered roller bearings inside), and so it works like a thrust bearing. This is in contrast to most (non-tapered) bearings which you encounter, which may quickly wear when exposed to end loads, depending on the bearings. Remember, we want a design that will work for hopefully years without too much intervention.

The other nice thing about this sort of spindle, complete with brake drum, is that the drum itself makes a nice place, magnetically and mechanically, to mount high-powered magnets and make your own alternator. The magnets are epoxied to the (cleaned) inside edge of the drum, some coils are wound and affixed where the magnets will excite them, and you have a setup with very few moving parts. Centrifugal force doesn't try to throw the magnets off of their mounting surface either, but rather presses them against it, so they can be simply stuck on with epoxy with no worries.

It's probably worth a trip to the junkyard to see about some front end parts like these if you plan to make your own alternator. My only advice would be to get parts from a car which you can still buy bearings for without too much trouble. After you've spent so much time building around a particular spindle, you don't want to find out that you can't find bearings for it later.

I have taken the off-the-shelf approach, with a 1" shaft and a couple of pillow-block bearings, with the idea being that the parts I use can be bought anywhere. Therefore, it's easier to convey what they are over the internet, and it's also easier when it comes to looking for a replacement bearing or whatever.

If you're turning an induction motor, then it will need to be turned just above its rated speed to work properly. You may also need to adjust the capacitance (most of them have external capacitors) so that they generate appropriately. I hear that the speed range of these motors can be narrow, so don't expect to turn one of these at, say, half its rated speed and get great results. Besides losing a good deal of the generation capacity, they may not generate at all, and probably won't.

Permanent magnet DC motors will indeed generate at almost any RPM. The question is how much power you will get out, of course. If you are trying to charge a 12V battery and you're turning the motor only fast enough to generate 10V, then of course you won't get anything useful. So the question becomes how the motor ratings affect what you can get out.

If you have, say, a 90V DC motor (some treadmills have these) rated at 3600 RPM and 6 amps, then the rules of thumb will be that the voltage will be proportional to the RPMs you turn it at, and that you can never exceed the amperage rating. This last point is the most important, and usually determines how much sense it will make to use a particular motor.

90V at 6 amps is 540 watts, and if you turned the motor at 3600 RPM and could use 90V then you'd have a suitable generator. However, if you can only use 14V and/or can only turn the motor fast enough to get 14V out, then your output will be limited to 14V x 6A, or 84 watts. You may be losing half that much to friction, though, and that's why people don't use overly large or mismatched motors a lot. It would probably be a better idea to go ahead and generate the higher voltage (90V) and then step it down with a switching power supply circuit, which has an efficieny of around 90%. This way you can get out the 14V at around 29 amps.

The key point here is that the amperage rating should not be exceeded on any sort of motor. Wires with too many amps passing through them get hot, and that's all there is to it. This is one of the reasons that success in wind generation is determined by matching, matching, matching! Wind speeds combined with desired outputs result in propellor sizes and coverages. Propellor RPMs and power plus desired output result in the kind of generator -- and possibly gearing and control -- that's appropriate.

Another item I have heard of is surplus computer tape drive motors, available for about $35 over the internet. These have brushes, so there is a little bit more than just bearings to wear out, but they'll make good power for a long time for a reasonable price. I have looked around the internet a bit, though, and these don't seem to be _readily_ available.

Some small engine starters have permanent magnets and would probably make suitable direct-drive generators. These have the advantage of being common and repairable. I'm not sure what RPM most of them would work well at, though, so they would require a little bit of experimentation. Look for ones with bearings instead of bushings... which might be a bit rare. The starters with bushings won't do well under continuous duty.

If you're going to generate 12V at the wind generator, you're certainly going to lose some power if you run that 12V a very long way without some very large wires. If you have free large wire, then more power to you, but keep in mind how much loss running your 12V a mere 100 feet can engender and plan accordingly.

At least the amperage is fairly low, and we can run it along long (and inexpensive) small wires without very much loss at all. At the other end, if we can use it directly in this form, that's good; otherwise we will probably incur another 10% loss by using a transformer to change it to a lower voltage, say for battery charging again.

Keep in mind that if you're going to use one of these setups, there must be almost no load on the motor until it self-excites and starts making juice. A small relay would probably be suitable to detect this; the coil will not present much of a load to the motor and it should excite ok, thus making electricity and closing the contacts to the load. Of course, if you are doing net metering (feeding power back to the utility system) then the utility power will provide the excitation and you need another system of determining when to make the connection.

My favorite configuration is a set of steel disks with matching magnets facing each other, and the coil(s) in the middle. Here you are guaranteeing that the magnetic field completes, largely through the coil in question, and that it is quite strong. The drawback, of course, is that this requires twice as many of these expensive magnets.

There is no rule requiring a certain number of magnets or a certain number of coils. If you have even one magnet passing by one coil, you're going to make power of some sort. Assuming that we're going to have a number of poles, what number to choose?

As with all things power-related, it's helpful if you create the electricity at roughly the voltage you need it. Of course, you can always put all of your coils in series to create the highest voltage, and if you have a distance to go from the turbine to the load, that might be the best thing to do (assuming single phase). If you're finding that your unit is producing ridiculously high voltages on a regular basis, ones you can't efficiently use, you may wish to parallel some of your coils.

Let's take an example with 12 magnets and 12 coils, all evenly spaced. All of the magnets are passing by all of the coils at the same time, so if they're all in series, you get the greatest voltage. Now take 2 sets of 6 coils each, in parallel, and you have half the voltage and twice the amperage. 3 sets of 4 and 4 sets of 3 work similarly of course. Of course I like the number 12 because it's easy to factor in this manner. :-) But I also think it's a reasonable number to work with insofar as size and cost go, for the home-made wind turbine.

Using a single 4-pole, double-throw relay, it would be easy to change, say, from 12 coils in series to 2 sets of 6 coils in parallel, depending on wind speed. I might prefer less mechanical and more electronic implementations, but the low-tech approach has the benefit of simplicity and ease of maintenance. Of course, this could be taken to extremes, and I don't suggest a whole bank of relays clicking about trying to do voltage regulation, as reliability might suffer.

There is no rule saying that you must have the same amount of magnets as you do coils. Almost any configuration will do, as long as any given set of coils are simultaneously actuated. It's not going to do much good to run a magnet by a coil if the next coil in the chain is not similarly actuated; you can see the sense in that. Similarly, don't have one string of 6 magnets actuated and another string of 6 connected in parallel with it unactuated. To keep power from "bouncing around" we need to use it or accumulate it in some manner right after making it.

Making 3-phase power is popular because 3 single phases add up well together and are therefore easier to rectify into purer DC. 6 magnets spinning past 18 coils would make 3-phase power, for example, where every third coil is connected in series to form one of the phases. I am not a great fan of 3-phase power generation in wind turbines because it is more difficult to run through transformers and the like. I like to play around with electronics, however, and if you merely want to generate power and immediately rectify it to DC then 3-phase is just fine.

The number of phases you generate also has something to do with the amount of vibration your unit is going to produce and subject itself to. If you are generating single-phase power, then all of the coils are generating electricity, and being subjected to pull, at the same time. This creates more vibration in the unit as a whole than if the power generation, and vibration, were divided up into thirds for example.

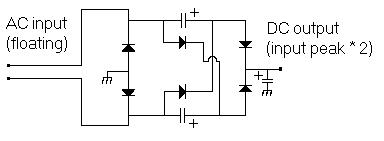

One possibility that you might investigate when implementing your own alternator is a voltage doubling circuit. This is a simple configuration which will change, say, 12V AC into 24V DC. Using this setup, you can always bump up your low-voltage AC to useful levels, and it's a lot simpler and probably just as efficient as, say, rewinding your wind generator. Of course, the current loading will be doubled, but if your alternator has sufficiently heavy wire this is not a problem. In any case, this is probably the sort of circuit you would switch in at low wind speeds to get some semblance of charging and you won't be putting much power through it.

Component values will depend on what you have kicking around or what you can afford. Usually it's safe to choose, for diodes, ones which will handle the desired current and at double the highest voltage expected. For the capacitors, ones rated at the highest voltage expected will do in this case, and the uf rating needs to be larger as the current drawn gets larger. What I'm saying is that these values aren't critical.

AC voltages can also be tripled, quadrupled, etc. with a similar sort of circuit. Search the internet for "voltage doubler" and "voltage tripler" to see this sort of circuit.

I need to put in a word for magnetsource.com, where I got my neodymium magnets. They had a pretty good deal on some poorly plated magnets and I figure I can paint them myself when things are all put together.

Eddy currents can occur in any "largish" piece of metal which is subjected to rapidly changing magnetic fields. Certainly the core of an alternator winding qualifies for this; the whole idea is to rapidly change the polarity of the magnetism at one end (or both) of the coil, and of course the core is the main conduit for this magnetism.

If you don't have magnets on both sides of an alternator coil, then it behooves you to at least place appropriate metal close to the unexcited end to act as a conduit to complete the magnetic field. It's important to realize that, because the magnetic field is also always changing in this piece (say, a ring) of metal, it too must be constructed in such as manner as to minimize eddy currents.

Most transformers are constructed with thin metal plates (laminations) which are enameled to insulate them electrically from each other. Since they are well intertwined, they still conduct magnetism just fine.

Unless you happen to want to cut and enamel your own laminations, you might go with a popular and widely available solution: pieces of enameled clothes hangar wire. This wire is already insulated with enamel, or at least paint most of the time, and is of the appropriate hardness already. I use coat hangar wire for everything else; why not for alternator coil cores? :-)

You may have read about "cogging", which is meant to describe the condition where the magnets attract the metal cores of the coils so strongly that it's hard to get the prop turning! Although metal cores improve the efficiency of coils (by acting as a conduit for the magnetic flux and coaxing more of it through the middle of the coil), this may not help if your turbine requires a blowing gale to start! If your prop has a smallish diameter or you know that your particular area is not blessed with high wind speeds, I'd leave the metal cores out so that the turbine can spin in low winds and at least have the possibility of making useful power.

I have spoken with the "distributed generation designated contact person" for my electric company, a very knowledgable fellow. The parameters for interconnection are that you must detect certain degrees of over and under voltage and over and under frequency at the interconnection point, along with some reasonable safeguards (breakers, disconnect switch accessible, etc.). They would also like to get the impression that your safety equipment will function correctly and continue to function after they test it and leave. If you have "certified" interconnection equipment then there is almost no testing at all, since the law says they basically have to approve it forthwith.

The local "retail provider" of electricity is clueless about net metering, but I've got an inquiry in and hopefully they're learning a bit more about it. If I actually have a working system ready to go, the law states that they must get me approved and connected within a certain time period, 30-90 days, I forget exactly. I am not submitting an application to start that process, however, without a bit more progress on this end.

I had an old electric meter kicking around, the mechanical kind that will spin backwards, and hooked it up to an extension cord for testing purposes. Turning a 1200 RPM induction motor geared up 2:1 by pulleys (yuck) with my 6' prop and decent winds, the meter did spin backwards -- not quite like a top, but power was certainly going in that direction. I guess a clamp-on ammeter might give a better real-time indication of how much power I was making. However, the 6' prop needed pretty good winds to get going because of the friction of the pulleys and the belt. The 8' prop did better but needed the same higher winds to turn quickly enough to make any juice. You can't win for losing! :-) I probably need to try a chain drive or something more sensible on this particular unit.

If you have 3-phase power at your place, or can arrange to get it connected, then you'll get a couple of benefits insofar as using induction motors as generators goes. Not only does your power company prefer that you generate 3-phase power, but 3-phase motors are generally more efficient. Also, because there is no capacitor or set of starting coils or the like, there is nothing to change or experiment with. You don't have to worry about bypassing starting switches or fooling with capacitor values.

3-phase motors can be easily reversed, usually by just reversing two of the wires, and that can be an important advantage. I wanted to mount my single-phase induction motor differently, and so changed the wiring like the plate on it said so it would run the other way. Well, it ran the other way as a motor... but I could never get it to generate in that direction! I'm not sure why, and was kinda curious... but I know that motor winding is a complicated subject, and possibly something about it escapes me.

Finally, three-phase motors are cheaper for some reason, especially when you get into the larger sizes. I bought a 2hp and a 5hp for $20 each recently, and had a new 1hp outright given to me. If they run when you connect them, then about the most you might have to do it replace the bearings to have good units. Also, I a fairly sure that they can be put to good use even if you don't have 3-phase power connections at your place. They can be run as motors off of single-phase power if you start them spinning manually, or attach the appropriate capacitors (they're somewhat derated, of course) and I'm fairly sure that means they'll generate fine too, although this may require using delta rather than wye connections. I'll check on this, or you can email me if you know more about it than I do. Meanwhile, you can look around on the internet for this sort of information.

You can find most of the Texas net metering laws in this PUC index if you know what you're looking for. Try 25.211 and 25.212 for starters.

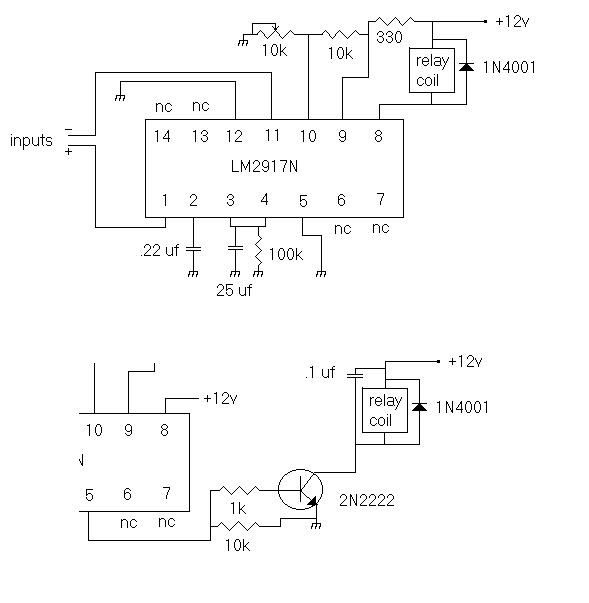

Texas law even specifically addresses/allows induction motors as a generation facility. You'd need a circuit to make the connection to the electric lines at the proper RPM, and it would have to be fairly accurate if you didn't want the thing using electricity instead of making it! Cutting in right at rated (1200, in this case) RPM would probably be acceptable, although 10-20 RPM more might be better. Here's a schematic for this sort of circuit, based on the LM2917N chip:

You want to measure the RPM of the induction motor directly, not the prop, and so for this I rigged up a magnetic pickup by taping a 1/4" chip of an old tape drive magnet to the flat part of the motor's shaft with a bit of electrical tape, then wound about 50 turns of smallish wire on the end of a 1/8" welding rod. The rod is bendable and easy to screw/bolt to something near the shaft, and each turn of wire generates about a millivolt at the RPMs we're dealing with here. The LM2917 chip requires about 30mv to properly actuate, and of course the more the better, to fight noise, but this pickup is not complicated and you can always fool with it. The voltage the pickup creates can be checked with any good meter.

You may ask youself why we don't just turn on a transistor or op amp at the proper speed by comparing the voltage the pickup generates with a reference. The problem with this is that it's not very accurate over extremes of temperature and the like, whereas the LM2917 chip, properly configured, is counting frequency itself and gives an accuracy of .3%, which should be good enough for our purposes. Use reasonably good components and you can expect adequate accuracy; probably the variable resistor will be the hardest component to keep stable.

The .22 uf capacitor can be experimented with so that your unit cuts in somewhere in the middle of your variable resistor's range. If you experience any chattering right at cut-in and cut-out, then increase the value of the 25 uf capacitor; the only down side of this is that the unit takes longer to cut in and out, so be reasonable.

The LM2917's output transistor can source or sink 50ma of current. If you have a larger relay you may wish to use the alternative output circuit described. It provides an output that goes positive upon actuation, instead of negative, and of course you could run whatever you wanted with it.

Some sort of feedback is usually desirable to produce some hysteresis in the operation, which will help cut down on chatter. Of course, you don't want too much of this, since your circuit can cut in at a fine RPM for making electricity, but fail to cut out when the RPM drops and begin to run as a motor, thus using electricity instead. Try connecting a 1 megohm variable resistor between pins 8 and 10 of the circuit described (4 and 5 for the second version) and experimenting with the amount of hysteresis appropriate for your setup.

Here is the datasheet for these chips. The 330 ohm resistor was chosen to keep a voltage of 7.56 at pin 9 with my particular power supply; usually 470 ohms is suitable. If you find your pin 9 voltage is significantly lower than 7.56 then drop this resistor's value a bit or bridge it with a 1k resistor and see what happens.

Most of the time that energy storage is mentioned, what's being referred to is the storage of electricity. It's important to think of what other uses you might come up with for the power though. I myself plan to run my electric hot water heater with a windmill. This is an ideal use, since over the course of a day, there is usually enough wind to heat the water up, hopefully by shower time! Since the heater has 2 elements, I can leave one connected to the utility power and turn it on when necessary; the second element is available to us. The point is that here we have a useful storage medium. Since my water heater costs me $35 per month or so to run, I figure it would be a real benefit to run it with wind power when possible, which is most of the time around here.

Old-style windmills use wind power directly to pump water up out of the ground; a rod moves up and down and pulls the water up directly. This is a fairly direct use of the wind power and is pretty efficient. I myself have the idea of using wind power to mechanically agitate a large tank of water; this should result in the heating of the water directly, without any intervening steps. In all of my searches of the internet, I've only seen this mentioned in one other place, probably because it would be difficult to agitate a pressurized tank. I've been thinking of elevating a tank somewhat and agitating that with a prop mounted above it -- maybe!

A company called Bowjon mounts small air compressors on windmills and runs the compressed air down into water wells. When the air bubbles out at the right depth, into the right diameter of pipe, it makes a pretty good water pump, and there are no moving parts to mention except for the air compressor! I like this idea, and as I am working on a cable tool rig for drilling my own water wells, I hope to actually get this setup going. Someone even gave me an original Bowjon compressor and the literature, although it seems like any air compressor would work.

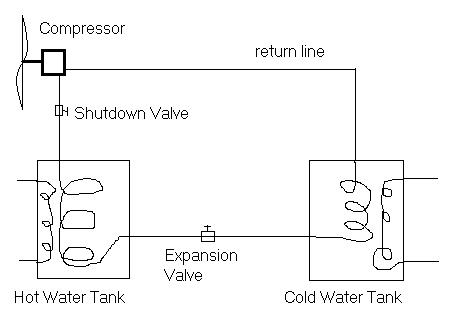

Another idea is to use the wind power to directly run a small air conditioning compressor. Nowadays most small A/C compressors are sealed units, with only the tubes and wires protruding, but the sort we're talking about looks like a small air compressor which is run by a belt. A friend of mine also says that old Delco car A/C compressors will work fine and are very durable.

Since compressors "generate" both heat and cold at the same time, a small compressor could, for example, heat a large tank of water and cool another large tank, so this heat and cold would be available when needed.

Please excuse the poor drawing of the coils in the tanks. :-) In any case, insulated tanks of some sort filled with water would probably do the trick. Filling them with bricks would store more heat/cold. The key accomplishment here is the generation of "cold" from wind power in the most direct manner possible, so that we avoid multiple conversion losses.

This is about the best way of getting cold out of a wind turbine that I can think of. Generating electricity, with which to run an air conditioner, is not likely to be practical. Can you imagine the size of the generator, batteries, and inverters it would take to run an air conditioner? :-)

I have a fairly popular page that does wind-related calculations

here.

I found a Windows program that does calculations here.

I like this page because the calculator these guys have works for several different types of wind turbines: Here

DIY Solar Panels For Your Home | How to Build Solar Panels